Being the Story Keeper – Part 1 – History

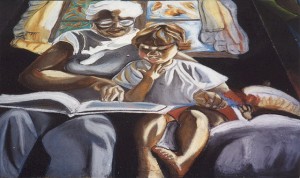

I remember as a child being a little fascinated with my baby book. Perhaps some of you remember looking at yours as well. In an analog world, it was a treasure trove of the things I couldn’t remember, and a view into my parents’ lives and the wonder they felt when I was born. I looked at it and felt not only amazed at my beginnings, but loved. I felt loved. My mother had taken the time to record all these things about me that told a story about the beginning of what I would become. Before I was old enough to be trusted with this treasure myself, I remember asking on occasion, “Can I look at my baby book?” Once in a while my mother looked at it with me, but most of the time I looked at it myself while she was busy with activities in our home; she worked multiple jobs so she was seldom without a to-do list to keep the house running. As she worked, she fielded questions and was amused by comments from me as I turned the pages.

For those of us raising adopted children, the story isn’t always such a thing of wonder. It can be a source of pain, confusion, and rejection. It is still, however, of critical importance. There are some things we just can’t sanitize, and I don’t advocate that we try. However, though perhaps afraid to ask, our children need to know their beginnings. It’s critical to their healing. Some of them remember vividly; others of them have fading memories. Being the Story Keeper means learning as much detail as we can, recording it, and presenting it in a way that helps them think in a balanced way about the realities…in a way that helps them process and face the hard things in a gentle and healing way, but also helps them embrace the good things as truly good, truly redemptive, and truly hopeful.

This is our responsibility, and it’s a tool of healing. As our children integrate into our families, we are to become a voice of truth over them. Here’s just one example: if our teenagers struggle with how they look (as teens often do), it’s up to us to hold up God’s word, put an arm around them and say with grace and firmness, “Darling, THIS is the truth. It’s right here, in The Book. You were made in the image of God; that makes you fully valuable and fully beautiful. THIS is the authority. What the world tells us is simply incorrect. This. is. truth. If you’re ugly, then so is the Lord in whose image you were made, and that just isn’t correct. You are an image-bearer, valuable, precious, and yes: beautiful.” You see, dear parent, that’s not us saying it. Did you ever hear, “You’re supposed to say that; you’re my mom”? No. This is the God of the very universe saying it. This is how we speak life and truth into and over our children.

In the same way we must approach their stories. Some of the truth is tough; they know that. They’ve lived it. However, there’s also redemption, protection, and more love than they might realize in their story. If you’ve been to my website, you know that I’m an advocate of life books. This is why they’re important. At some point, our children want to know the parts of their story that they don’t remember. We used to tell my son about coming into our family as though it were in a book. “Once upon a time…” Soon, he was asking us, “Tell me a story about the little boy from Haiti!” He knew it was about him. Each person in our family told it a little differently, with a few details that the next person didn’t include, and in a perspective unique to them. We didn’t sanitize it. We shared that he was a very ill little boy, that his birth mama was afraid that he was too ill to live, and that she took him to a place where he could get the help he needed. We talked about birth mama and her challenges right away, age appropriately, as well as the good parts. Here’s the value in a life book: as your child’s Story Keeper, it gives you a go-to place when questions come. There are things you won’t know, but record as much as you can find out and work to make it a tool of healing. Here are a few thoughts when it comes to being the Story Keeper:

- Theology is critically important. Our kids need to understand that we live in a fallen world. This will help them understand that some things aren’t their fault, and that they are indeed valuable. Hard things happen as a result of our fallen state of being. Additionally, proper theology will help instill a perspective of value into them. How’s this for truth: before the foundation of the world, Jehovah himself had his hand on each and every one of us, including our children. Mighty, life giving truth is found in Psalm 139. Verses 13 and 14 are often quoted, but verse 16, “your eyes have seen my unformed substance,” tells us that He saw us before we even came to be. He saw us. He placed value on us. He loved us. Equally important: if God is grieved over sin (as the Bible teaches) and hurt and pain, then He hurts with and on behalf of our children in the dark parts of their story, and His anger burns against those who would wound the vulnerable. He hurts over the hurts of their birth parents, and the brokenness of their stories as well. And as our children come to us, He has also worked out a way of safety, security, love and healing for them. That’s important theology, and it creates a place for healing in their stories.

- Truth in love. There are some things you just can’t sanitize, and we shouldn’t. Abuse is a reality, horrid and nauseating and tremendously damaging. Relinquishment because of poverty and disease is gut-wrenching and heart breaking. However, I don’t recommend writing down the more sordid details of our children’s histories. Truth in love to me means a couple of things. First, it means that some things are better as conversations, during which you can convey tenderness and carefulness through tone and tempo. “Birth mama didn’t have enough money to feed you so that you would live,” isn’t something we want our kids to read without an opportunity for dialogue. (I know…none of us would actually write it that way, but you see my point.) Truth in love means making time for these conversations in a loving and safe context, and allowing our kids to share what they think and feel about them. It means taking time to let them ask the hard questions, and sitting together in the simple and visceral “wrongness” of the fallen nature of a world that makes unimaginable circumstances reality for some. It means acknowledging the pain that’s there. It’s so valuable for our kids to know that we don’t view their stories only for their value to us and the joy of having them in our family. They need to know that we have sorrow over the things they have experienced, and that we acknowledge that those things are sad and difficult, and that yes, we even wish that although God has provided a way to healing, we wish they hadn’t had to experience these things to begin with.

- Make it regular. Part of being a Story Keeper is helping our kids continue to build their stories, as well as acknowledging the good parts of what has already come to pass. Are there funny things that happened when they came into your home that you can all enjoy memories of? Mention them when the context allows. Do you have pictures from your referral, or the first couple of times when you met them? Mention your positive impressions of them then. Our son likes to know that we noticed and loved his dimples and birth mark when we got the first photos of him, for example. You stare in awesome wonder at an adopted child’s beauty and being just as you do a birth child; this is part of their story. Lastly, keep recording. A life book doesn’t have to stop at a specific age. Age appropriately, continue to add milestones and memories made as life continues with your child.

There’s so much to being the Story Keeper. Bottom line: do what works for you and your child in your own family context to help bring healing and perspective for your child, but make sure that includes acknowledging their history in a way that will contribute to their sense of safety, value, and growth. Own their story; be their safe and loving Story Keeper until they are old enough and healed enough to own their story themselves in their way.

Comments are closed.